Who is Tevfik Arif? Part I

Who is Tevfik Arif? Part I

Figuring out who he is was not an easy task.

Tevfik Arif (Тевфик Ариф) was born Toifik Arifov (Тофик Арифов) on May 15, 1953 in the Soviet Socialist Republic of Kazakhstan. He was one of four brothers born to a Turkish family in the Jambyl Region in northern Kazakhstan.

That’s about the only thing we know about his early life with any certainty.

What he did for the next 38 years is unclear. The oft-repeated facts of his background come from a short profile on Arif published in Real Estate Weekly in 2007, just as Trump was preparing to kick off sales of Trump SoHo.

Real Estate Weekly reported that Arif had received a degree from Moscow Institute of Trade and Economics and then worked in the Soviet Ministry of Commerce and Trade in the former Soviet Union for 17 years, where he served as the chief economist and deputy director of the Ministry’s Department of Hotel Management.

Many journalists have repeated this story. It may be true, but no one seems to have bothered to check. It’s worth noting that this is the reference to a Soviet Ministry of Commerce and Trade that I found on the Internet. There is a Russian ministry that has this name, but I could find nothing from the Soviet era. (Arif did not speak English very well, so it’s possible this is a mistranslation.)

There was, however, something called the USSR Chamber of Commerce and Industry, which was run by the KGB and spied on the West. A third of the chamber’s staff were KGB, according to a US State Department report that cited CIA information. And the USS Chamber of Commerce and Industry did have a hotel division, V/0 Sovintsentr, which ran a trade center and various Moscow hotels.

In the Russian press, Arif is affiliated with the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Trade (which did exist). Or maybe he was just a Soviet hotel bureaucrat, as he claims. Whatever Arif did for the first 40 odd years of his life, he hasn’t been very open about it.

Trans World Group

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Arif left the government and made a career leap. A huge leap.

In a court proceeding in Turkey, the former Soviet hotel bureaucrat testified that he “worked in energy sector, chemical sector and metallurgy sector. I was producing coal in Russia and copper in Kazakhstan. Due to lack of coal, it was not possible to make production. I started to organize them.” He started a private company called the Speciality Chemicals Trading Co., trading in “chrome, rare metals and raw materials.”

And then he went to work for Trans World Group. TWG was a British company headed by two brothers, David and Simon Reuben. After the Soviet Union collapsed, the Reubens moved aggressively into metals production, buying up smelters and refineries.

As foreigners, however, the Reubens needed locals to build their business. Enter Arif. He became an “agent on the ground” — a fixer, in other words — for TWG in Kazakhstan, according to internal company documents reviewed by theblacksea.eu, an online investigative Website.

Arif apparently did his job well. Very well. In a few years, TWG’s holdings of steel, iron, chrome and alumina refineries in Kazakhstan generated one fifth of the entire country’s gross revenues.

Maybe Arif was just a Soviet hotel bureaucrat who seized a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to get into the post-Soviet metals sector. But his hotel background would have been of little use to TWG. What TWG needed was someone with deep connections in the country’s political and business circles. The kind of people who had those connections in the Russia of the 1990s were either ex-KGB, or mobsters.

Michael Cherney

Consider another pair of fixers the Reubens brought into TWG in 1992. They were the Cherney brothers, Lev and Michael, and they formed a 50-50 partnership with TWG. It was a successful partnership. With the Cherneys help, TWG grew by leaps and bounds. The problem for the Reubens was that Michael Cherney’s name soon became publicly linked to Russian organized crime groups. The Reubens quickly bought out Cherney’s share of TWG for $410 million.

Vyacheslav Ivankov

Swiss authorities in 1996 accused Michael Cherney of “drug trafficking, money laundering, fraud and sponsoring murder” on behalf of a Russian organized crime group run by “V Ivankov.” This was the infamous Russian mob boss nicknamed “Yaponchik” who had settled in New York, where the FBI found him hiding out in Trump Tower and Trump’s New Jersey casino.

Michael Cherney has repeatedly denied these allegations, which he blames on his archenemy and former partner Oleg Deripaska, one of the wealthiest men in Russia. In 2008, the federal Swiss court exonerated him of the charges, but two years later, Spain issued an international arrest warrant for Michael Cherney’s arrest on money laundering charges.

Did Arif have links to the Russian Mafia? Felix Sater, who worked under Arif at Bayrock, seems to think so.

The Wall Street Journal reported that Sater and his attorney threatened to expose Arif’s past unless he paid Sater’s attorney fees. Sater warned of a possible lawsuit that would include details of Arif’s wrongdoing “in the post-Soviet metals business in Kazakhstan.”

In a personal memo, Sater was even more blunt: “The headlines will be, ‘The Kazakh Gangster and President Trump.’”

A High-Net Worth Individual

“The head of the family is my uncle Roustam Arif [sic],” Tevfik’s son Arif writes in 2013 in correspondence obtained by theblacksea.eu. “In our culture, the patriarch is usually the oldest member of the family. Roustam is my father’s oldest brother. Even though my father is a successful entrepreneur in his own right (hotels, construction and real estate), his younger brother Refik Arif is the principal figure in the main family business (commodities).”

In the mid-90s, Refik reportedly acquired control of the Aktyubinsk Chromium Chemicals Plant (ACCP) in Aktobe, in north-western Kazakhstan, near the border with Russia. Refik also established a highly profitable chemicals trading business. And this is an important piece of the story, because the money for Bayrock, at least part of it, came through Kazakhstan.

Consider that for a moment. The Arifs managed to pool enough capital and influence to buy what turned out to be a highly lucrative chemical plant. How was this possible? What really happened in Kazakhstan in 1990s?

Around 1999, Refik Arif’s chemical trading business was generating so much cash that the family retained Hamels, a UK tax consultancy, to help structure their investments. On its website, Hamels describes its typical clients as “high net worth individuals seeking to minimize their respective tax burdens on current income or investment streams…”

In a 2011 memo, Hamels partner Zig Wilamowski wrote, “Mr. Refik Arif is one of four brothers who have over many years built up a substantial and profitable international business from the sale of chrome-based chemicals.” Williamowski said he was in a position to verify the “good origin” of the Arif family’s wealth. You can read the document here.

With the help of Hamels, the Arifs set up a network of shell companies, many of which were established in the Caribbean tax haven of the British Virgin Islands. These companies included Bennington Trade Assets Ltd., which owns property in the center of London and Merlin Trading Assets Ltd., which owns an executive jet. There are too many companies to name them all. Many are found in the Panama Papers leak of offshore companies founded by the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca.

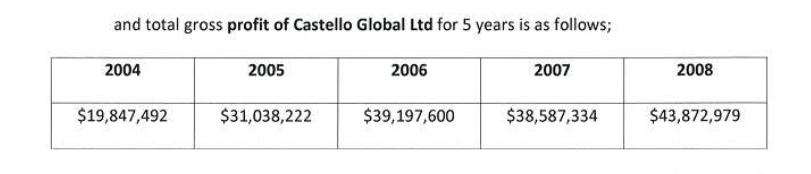

The real moneymaker for the family was Castello Global Ltd., which handled the profits from the chrome trading business. Here is a breakdown of Castello Global’s profits:

So much money was pouring out of Kazakhstan that Tevfik Arif decided it was time to try something big. Really big.

He moved to New York and set out to do a real estate deal with the biggest and the best. So he set up offices of his new company Bayrock Group in Trump Tower, one floor below Trump’s own offices.

To be continued…

Rodrigo Pena

Смотреть все новости автора